tags: bpr3.org/?p= 52, Early Bird Project, Tree of Life, avian evolution, deep avian evolutionary relationships, avian phylogenomics, location cues, Shannon J. Hackett, Rebecca T. Kimball, Sushma Reddy

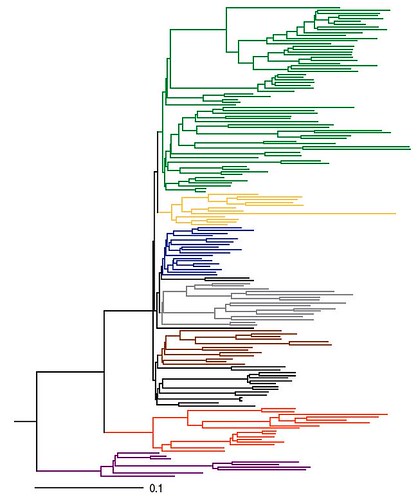

Basic topology of the evolutionary relationships between birds.

Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogram reveals the short internodes at the base of Neoaves and highlights certain extreme examples of rate variation across avian lineages. The phylogenetic tree was rooted to crocodilian outgroups (not shown). Branch colors represent major clades supported in this study: land birds (green), charadriiforms (yellow), water birds (blue), core gruiforms and cuckoos (gray), apodiforms and caprimulgiforms (brown), galloanserae (orange), and paleognaths (purple). Scale bar indicates substitutions per site.

Image: SJ Hackett et al. DOI: 10.1126/science. 1157704.

[larger view].

A fascinating paper was just published by some of my colleagues in the top-tier journal, Science, that analyzes the largest collection of DNA data ever assembled for birds. This analysis effectively redraws avian phylogeny, or family tree, thus shaking up our current understanding of the early, or "deep", evolutionary relationships of birds. For example, one of the most surprising findings of this analysis is that parrots and songbirds are "sister groups" -- each other's closest relatives!

And here's another surprise; falcons are the sister group to the parrots and songbirds. Further, the falcons (Falconidae) include the New World vultures -- but they are not closely related to eagles, hawks and osprey (Accipitridae) , as previously thought.

So why is avian taxonomy suddenly in such a state of upheaval? The precise evolutionary relationships between major groups of birds have long been contentious because they underwent an explosive radiation event sometime between 65 million and 100 million years ago. Nearly all of the major avian groups arose within just a few million years -- a very short period of evolutionary time. As a result, those groups of birds, such as parrots, doves and owls, that are united by distinct morphological characteristics seem to have appeared suddenly because there are few, or no, known evolutionary intermediates that provide clues to their deeper relationships with other avian groups.

These new findings are important because much of our scientific knowledge about reproductive biology, speciation, behavior, ecology, and natural history of animals is based on our studies of birds, so these data provide a new evolutionary framework that can be scientifically tested for decades to come.

This research, which was carried out over a period of five years by an international group of 18 scientists known as the Early Bird Assembling the Tree-of-Life Research Project, represents the most extensive genome-level analysis for any group of animals so far. Interestingly, the three lead authors of this study are female and more than half of "the Early Birds" are women.

To do this work, the Early Bird group examined 19 independent loci consisting of 32 kilobases of nuclear DNA sequence obtained from 169 avian species representing all major groups of birds alive today. These nuclear loci included introns (74%), exons (coding regions, or "genes") (23%), and untranslated regions (UTRs) (3%) across 15 different chromosomes (according to the chicken genome). These DNA sequence data were subjected to multiple statistal analyses that produced a robust phylogeny.

These analyses reveal two major findings: First, the classifications and conventional wisdom regarding the evolutionary relationships among many birds is wrong. Second, birds that have similar appearances or behaviors are not necessarily related to each other. According to these data;

- Birds adapted to different environments, such as terrestrial or ocean life, several times.

- Distinctive lifestyles evolved several times. For example, contrary to conventional thinking, the colorful, daytime hummingbirds are a specialized subgroup of the drably colored nocturnal or crepuscular nightjars; falcons are not closely related to hawks and eagles; flighted tinamous arose from the flightless rheas and ostriches; and tropicbirds are not closely related to pelicans and other waterbirds.

- Shorebirds are not a basal evolutionary group, which refutes the widely held view that shorebirds gave rise to all modern birds.

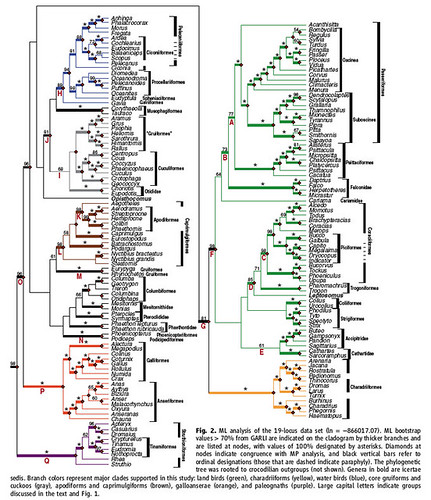

This phylogeny both confirms and challenges our current understanding of the relationships between the majority of bird groups as determined primarily on the basis of morphological analyses (figure 2);

Figure 2: ML analysis of the 19 loci data set. ML bootstrap values > 70% from GARLI are indicated on the cladogram by thicketr branches and are listed at nodes, with values of 100% indicated by asterisks. Diamonds at nodes indicate congruence with MP analysis, and black vertical bars refer to ordinal designations (those that are dashed indicate paraphyly). The phylogenetic tree was rooted to crocodilian outgroups (not shown). Branch colors represent major clades supported in this study: land birds (green), charadriiforms (yellow), water birds (blue), core gruiforms and cuckoos (gray), apodiforms and caprimulgiforms (brown), galloanserae (orange), and paleognaths (purple).

Image: SJ Hackett et al. DOI: 10.1126/science. 1157704 [larger view]

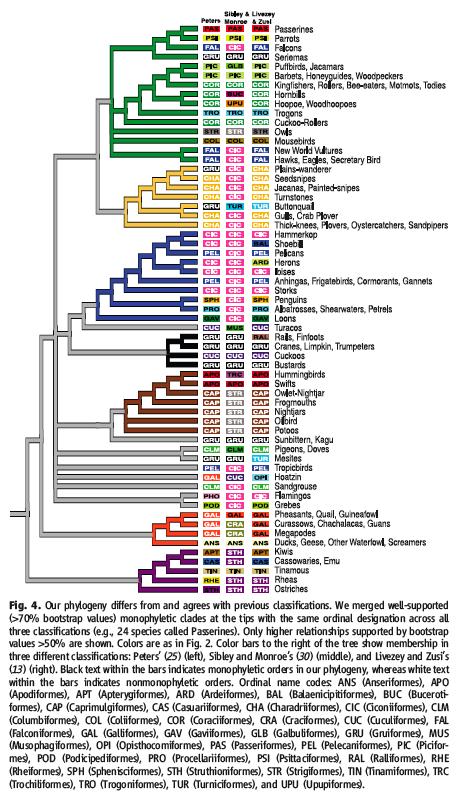

In a nutshell, this research confirms two previous taxonomic classification schemes that were based on morphological studies (also refer to Figure 4, below);

- Aves consist of two main groups: Paleognathae (ratites and tinamous) are separate from Neognathae (all other birds)

- Neognathae are split into two groups; the Galloanserae (ducks, chickens and their allies) and the Neoaves (other neognaths)

However, this research also challenges many of our current taxonomic schemes (Figure 2, see also Figure 4, below);

- The largest clade within Neoaves consists of the landbirds (green): Passeriformes (songbirds), Piciformes (woodpeckers and allies), Falconiformes (falcons), Strigiformes (owls), Coraciiformes (kingfishers, hornbills, rollers and allies), Psittaciformes (parrots), Coliiformes (mousebirds) and Trogoniformes (Trogons). Landbird surprises include;

- Parrots and songbirds are sister groups.

- Falcons are the sister group to parrots and songbirds.

- Falcons (Falconiformes) are a distinct clade from the eagles, hawks and osprey (Accipitridae) .

- New World vultures (Cathartidae) do not belong in the storks and allies (Ciconiiformes) , but should instead be included with the falcons (Falconiformes) .

- Woodpeckers (Piciformes) are a specialized grouping within the kingfishers, hornbills, rollers and allies clade (Coraciiformes) .

- Seriemas (Cariamidae) are sister to the falcons not the Gruiformes.

- The sister group to the landbird clade are the waterbird clades: Charadriiformes (shorebirds, gulls, and alcids) (yellow), and the Pelecaniformes (totipalmate birds), Ciconiformes (storks, herons, bitterns and allies), Procellariiformes (tube-noses) , Sphenisciformes (penguins), and Gaviiformes (loons) (all blue). Additionally;

- Buttonquail, Turnix species, belong within Charadriformes.

- Pelicans (Pelecaniformes) and storks, herons, bitterns and allies (Ciconiformes) form one clade.

- The tropicbirds (Phaethontidae) , which were previously classified within the pelicans (Pelecaniformes) , are now excluded from the newly identified Pelecaniformes- Ciconiformes clade.

- Some other revelations include;

- Hummingbirds and swifts (Apodiformes) are found within the nightjar clade (Caprimulgiformes) .

- Sunbitterns (Eurypygidae) , which are neotropical species, and the mysterious New Caledonian Kagu, Rhynochetos jubatus, are sister taxa that are not found within Gruiformes.

- Grebes (Podicipediformes) and flamingos (Phoenicopteriforme s) are sister taxa.

- Tinamous (Tinamiformes) , which are flighted, arose within the flightless Struthioniformes (rheas, ostriches, cassowaries, emus and kiwis)

Yet, despite the large sample size and the rigor of the analyses, there's still a few avian mysteries whose relationships remain unresolved;

- Hoatzin, Opisthocomus hoazin -- just what is this creature??

- Pigeons and doves (Columbiformes) .

- Sandgrouse (Pteroclididae) .

- Tropicbirds (Phaethontidae) .

- and the appropriately named mesites (Mesitornithidae) , is a family of birds of uncertain affinities (this is sometimes known as the "taxonomic garbage can"). On the the hand, since the three mesites species are all endangered anyway, perhaps they all will be wiped out forever, so we no longer have to worry about how they fit into the evolutionary tree for birds?

These new data correspond for only six avian orders when compared to two studies that were published earlier; Sibley and Monroe's DNA-DNA hybridization study (1990) and Livesey and Zusi's comparative anatomy study (2007) (figure 4);

Image: SJ Hackett et al. DOI: 10.1126/science. 1157704.

In light of these new data, comparative studies of birds will benefit from increased rigor and will yield greater insights into the process of evolution and speciation. This research also affect publishers and birders because biology textbooks and birdwatching field guides will have to be rewritten.

Notes on the phylogeny and questions for the Early Birds:

- What happens if you remove Leptosomus (Clade D)? Does this clade resolve with stronger support without it included in the analysis?

- I am surprised that the connection between Passeriformes and Psittaciformes and the connection between Passeriformes- Psittaciformes and Falconiformes are being taken so seriously when they have such low bootstrap support [but see Ericson et al. (2006) DOI: 10.1098/rsbl. 2006.0523]. What gives? What would happen to the analysis if the Falconiformes were removed? How much rearranging of the Passeriformes, Psittaciformes and Charadriiformes within the tree itself would occur?

- Which gene(s) place seriemas within Falconiformes?

- Accipitridae show abberant behavior in molecular phylogenies, and everyone agrees that this lineage is old, and the bootstrap support for this clade is not strong.

- The fossil record strongly suggests that the Charadriiformes should precede Ciconiiformes along with a few other avian orders, and the fossil record for Turnix suggests it predates gulls and alcids. And wow, I thought sandgrouse were located within this clade?? Which gene(s) relocated them?

- Have you noticed that, if Charadriiformes is removed, the support for much of the tree is lost. What gives here?

- There is surprisingly poor taxon sampling for the non-Passeriodea Passerida.

- I am disappointed by the really poor bootstrap support for the Columbiformes node .. knowing the placement for this order would really help clarify our understanding of avian relationships in general.

- The placement of Tinamous within the ratites instead of being basal to them suggests either that flight was lost and gained several times in the evolutionary history of birds or that flight was lost independently many times, but only within the ratites. Interesting!

Source:

Hackett, S.J., Kimball, R.T., Reddy, S., Bowie, R.C., Braun, E.L., Braun, M.J., Chojnowski, J.L., Cox, W.A., Han, K., Harshman, J.,

Huddleston, C.J., Marks, B.D., Miglia, K.J., Moore, W.S., Sheldon, F.H., Steadman, D.W., Witt, C.C., Yuri, T. (2008). A Phylogenomic Study of Birds Reveals Their Evolutionary History. Science, 320(5884), 1763-1768. DOI: 10.1126/science. 1157704.

Also see:

Ericson, P.G., Anderson, C.L., Britton, T., Elzanowski, A., Johansson, U.S., Källersjö, M., Ohlson, J.I., Parsons, T.J., Zuccon, D., Mayr, G. (2006). Diversification of Neoaves: integration of molecular sequence data and fossils.

Biology Letters, 2(4), 543-547. DOI: 10.1098/rsbl. 2006.0523.

Comments

I thought the early bird got the worm?

(Sorry, couldn't resist!)

Posted by: Jeb, FCD | June 26, 2008 7:22 PM

HOLY SMOKES! Bird phylogeny will never be the same. I saw this post and skimmed it fast, thinking oh great, another phylogeny which changes up everything, how is this one any different, but then I saw they used 19 LOCI! Wow. I am in awe. Good work, Hackett et al. Thanks for bringing this to my attention. I think I'm going to spend half the night poring over it.

~ Nick

Posted by: Nick | June 26, 2008 8:14 PM

Thanks for this thorough report on the Science paper and for including the cladograms. It will be interesting to see what the various checklist committees do with the results.

Posted by: John | June 26, 2008 8:42 PM

"The phylogenetic tree was rooted to crocodilian outgroups (not shown)"?????

I thought that it was widely accepted that birds are the last dinosaurs. Or are dinosaurs "crocodilian outgroups?"

Posted by: Bob Wright | June 26, 2008 10:49 PM

No, crocodilians are dinosaur outgroups. Crocodilians are, however, the closest available outgroup for molecular analysis of birds, seeing as everything closer has been extinct for too long for much molecular data to be available.

Posted by: Christopher Taylor | June 26, 2008 11:45 PM

How does the "tastes like chicken" trait map onto the tree?

Posted by: Bob O'H | June 27, 2008 1:07 AM

Or rather, flight was lost three times independently within paleognaths: once in ostriches, once in rheas, and once in kiwis + emus + cassowaries. .. or rather twice within the latter clade, because imagining a kiwi rafting from Australia to New Zealand is a bit hard.

But the position of the ostrich in the tree is suspect anyway -- it looks like long-branch attraction. Look at Fig. 3, the one on top of this blog post: the ostrich is the purple branch at the very bottom. That the ostrich has a faster rate of molecular evolution than usual has long been known.

Posted by: David Marjanović | June 27, 2008 5:03 AM

There might even be long-branch repulsion between the ostrich and the remarkably long branch at the base of the tinamous.

Posted by: David Marjanović, OM | June 27, 2008 5:15 AM

Preliminary conclusions were presented at the paper session of the Minnesota Ornithologists Union that I attended this Spring. As the conclusions were introduced, the sounds of those in the auditorium murmuring around me fell away, and visually everything became blurred out except the presenter and the phylogeny on the screen as my perceptions of how evolutionary processes must have produced these birds shifted, blew apart and refused to settle back down into coherence. Thank you so much for your post on this subject.

Posted by: Kathy | June 27, 2008 9:27 AM

You said:

Further, the falcons (Falconidae) include the New World vultures -- but they are not closely related to eagles, hawks and osprey, as previously thought.

..but later explain that New World vultures are actually in Accipitridae after all.

Posted by: Rich | June 27, 2008 12:31 PM

OOPS! thanks for spotting that error.

Posted by: "GrrlScientist" | June 27, 2008 12:39 PM

1. I don't see how a flightless bird can re-evolve flight. Impossible I would have thought.

2. How can you tell from DNA that the common ancestor of the hummingbirds and nightjars was nocturnal?

Posted by: John Leonard | June 27, 2008 6:56 PM

You wrote:

Did you actually mean that Seriemas are sister to the grouping of falcons, parrots, and passerines? That's how it appeared to me.

Also, how does one explain, from a biogeographical approach, the locations of the sunbittern and kagu if they are sister to one another... Gondwanaland was split far too early for the ancestor of this clade to have occupied the entire continent, right? Does one invoke island hoping? The new world tropics are a bit removed form New Caledonia.

Excellent writeup. Thanks so much for including the figures!

Posted by: Jay | June 27, 2008 7:18 PM

Not from DNA, but from the tree: either a nocturnal lifestyle evolved several times independently in this clade, or it evolved once and reversed once. The principle of parsimony favors the latter hypothesis.

------------ -

New Caledonia and South America were connected via New Zealand and Antarctica till 88 million years ago, which is way too early, but the sunbittern can fly, and the connection between South America and Antarctica only broke 37 or so million years ago...

And aren't there fossil sunbitterns in the early Eocene of North America?

Posted by: David Marjanović, OM | June 27, 2008 7:58 PM

I should have mentioned that the New World tropics weren't far removed from Antarctica 40, let alone 55, million years ago. Paratropical rainforest ( = with a short dry season) extended into Antarctica even.

Posted by: David Marjanović, OM | June 27, 2008 8:18 PM

Fantabulous! A feather in your cap for writing it up for us.

Posted by: Monado | June 27, 2008 9:53 PM

'How can you tell from DNA that the common ancestor of the hummingbirds and nightjars was nocturnal?'

'Not from DNA, but from the tree: either a nocturnal lifestyle evolved several times independently in this clade, or it evolved once and reversed once. The principle of parsimony favors the latter hypothesis.'

Why can't it have evolved once, after the split between hummingbirds and nightjars?

Posted by: John Leonard | June 27, 2008 9:54 PM

We know from both molecular and morphological data that Apodiformes (swifts and hummingbirds) , which are diurnal, are nested within Caprimulgiformes (nightjars and allies) rather than being their sister group. So therefore if nocturnality (if that's a word) evolved in nightjars after they split from Apodiformes, it would have had to have evolved independently in owlet-nightjars, oilbirds and frogmouths - owlet-nightjars are more closely related to Apodiformes than nightjars, while oilbirds and frogmouths are less closely related to Apodiformes. As David pointed out, there would have been less changes in lifestyle involved if diurnality is a reversal in Apodiformes than if it evolved separately in each of the caprimulgiform families.

Posted by: Christopher Taylor | June 27, 2008 10:46 PM Having problems commenting? (UPDATED)